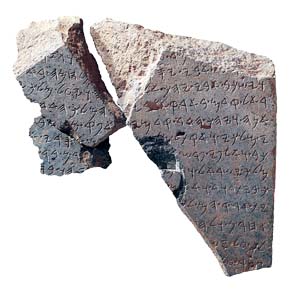

Photo: Tel Dan Inscription

It has been a popular view among many people that the Bible proves the historical events of the Bible. It is said that William F. Albright, the famous American archaeologist of the twentieth century, sought to prove the historicity of the Bible by digging in Israel with a shovel on one hand and the Bible on the other.

In the last two decades or so, the traditional conclusions of archaeologists have come under severe attack by other archaeologists who believe that the archaeological evidence does not confirm many of the historical facts found in the Bible.

The claim and counterclaim of archaeologists in recent years have been focused on the archaeological significance of Khirbet Qeiyafa, a site located in the Valley of Elah, the place where David killed Goliath. And the two archaeologists involved in this dispute are Yosef Garfinkel, the co-director of the dig at Khirbet Qeiyafa, and Israel Finkelstein, a professor of archaeology at Tel Aviv University.

In a recent article, “What archaeology tells us about the Bible,” Christa Case Bryant, a staff writer for The Christian Science Monitor summarizes the issues in this controversy:

Mr. Garfinkel, a professor at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, examines the coin, the size of a thick quarter. He smiles. Each discovery delights Garfinkel, but it is more than ancient currency that has drawn the world’s attention to this serene hilltop overlooking Israel’s Valley of Elah, where David felled Goliath with a sling.

Instead, it is what Khirbet Qeiyafa has revealed about David’s reign, about the emergence of ancient Israel, and, by extension, about the historical accuracy of the Bible itself.

For the past 20 years, a battle has been waged with spades and scientific tracts over just how mighty David and the Israelites were. A string of archaeologists and Bible scholars, building on critical scholarship from the 1970s and ’80s, has argued that David and his son Solomon were the product of a literary tradition that at best exaggerated their rule and perhaps fabricated their existence altogether.

For some, the finds at Qeiyafa have tilted the evidence against such skeptical views of the Bible. Garfinkel says his work here bolsters the argument for a regional government at the time of David – with fortified cities, central taxation, international trade, and distinct religious traditions in the Judean hills. He says it refutes the portrayal by other scholars of an agrarian society in which David was nothing more than a “Bedouin sheikh in a tent.”

“Before us, there was no evidence of a kingdom of Judah in the 10th century [BC],” says Garfinkel. “And we have changed the picture.”

But critics question his methods on the ground and his interpretations in scholarly journals.

The dispute transcends the simple meaning of ancient inscriptions found at Qeiyafa, or the accuracy of carbon-dating tests on olive pits. It highlights the whole dynamic between archaeology and the Bible – whether science can, in fact, help authenticate the Scriptures.

“If you are in the trenches of what’s going on today, the battle for Qeiyafa looks very important,” says Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University and one of Garfinkel’s most prominent critics. “But if you are zooming out, you see that all this is another phase in a very long battle for the question of the historicity of the biblical text, for understanding the nature of the Bible, for understanding the cultural meaning of the Bible.”

Bryant continues her article by providing an extensive discussion on the controversy between those archaeologists who believe that archeology has much to contribute in demonstrating the historicity of the biblical narrative and those archaeologists who deny that the Bible contains accurate historical facts.

Bryant’s article is worth reading because she quotes archaeologists on both sides of the dispute. Time and space does not allow me to discuss all the issues covered by Bryant’s article. If you want to gain a better understanding of this important controversy among archeologists, you should read this article. You can read the article here.

Personally, I believe that archaeology has much to contribute to the understanding of many of the historical narratives of the Bible as well as to the proper understanding of the social practices of ancient Israel.

However, we must understand that the testimony of archaeology is mute, that is, stones do not speak. The evidence of archaeology must be interpreted by archaeologists and archaeologists are human beings who are influenced by their cultural, political, and religious views. These views affect the way one looks at the evidence.

Above I mentioned William F. Albright. Albright was a Christian archaeologist who believed in the historicity of the biblical narratives and to him, archaeology helped confirm some of the historical facts of the Bible. If the archaeologist is a secular person, then he or she will see the Bible as the creation of a religious people. Thus, whatever the Bible says, it needs the confirmation of secular sources to authenticate its historical narratives.

One good example of this archaeological bias is seen in the interpretation of the Tel Dan Inscription, also known as “The House of David Inscription”. The Tel Dan Inscription mentions “the house of David.” Until the time the inscription was found, secularists said that David, Solomon, and the united monarchy were invented fiction to prove Israel’s glorious past, a glorious past that never existed.

When the Tel Dan Inscription was found, mentioning for the first time the name of David outside the Bible, those who deny the historicity of the biblical events created all kinds of theories to disprove any reference to David. Thus, an important archaeological discovery was interpreted in different ways by biblical scholars. And this is the same problem one finds when seeking to understand the significance of Khirbet Qeiyafa for biblical studies and how archaeology can help us understand the Bible.

I hope you will read Bryant’s article.

NOTE: For other articles on archaeology, archaeological discoveries, and how they relate to the Bible, read my post Can Archaeology Prove the Bible?.

Claude Mariottini

Emeritus Professor of Old Testament

Northern Baptist Seminary

NOTE: Did you like this post? Do you think other people would like to read this post? Be sure to share this post on Facebook and share a link on Twitter or Tumblr so that others may enjoy reading it too!

I would love to hear from you! Let me know what you thought of this post by leaving a comment below. Be sure to like my page on Facebook, follow me on Twitter, follow me on Tumblr, Facebook, and subscribe to my blog to receive each post by email.

If you are looking for other series of studies on the Old Testament, visit the Archive section and you will find many studies that deal with a variety of topics.

Pingback: Archaeology and the Bible | A disciple's study

“One good example of this archaeological bias is seen in the interpretation of the Tel Dan Inscription, also known as “The House of David Inscription”. The Tel Dan Inscription mentions “the house of David.” ”

this is not proof David was real, the Japanese Emperor claims to have descended from Amaterasu the sun goddess, and since the there are ancient records of his ancestors making this claim does this mean that Amaterasu is real? The tablet can only prove people believed that David was real

LikeLike

Tony,

You may be right, but the archaeological evidence is strong because the Tel Dan Inscription was not written by anyone in Israel. The Tel Dan Inscription is like the Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, and Hittite monuments. The Cyrus Cylinder mentions Cyrus and he was an actual historical person. Egyptian monuments mention Ramses and he was a real historical person. The Stele found at Tel Dan also mentions a real historical person. The Moabite Stone, another document from another time also mentions David. This alone seems to indicate the David was not a fictitious person.

Claude Mariottini

LikeLike